I suppose we must each ask of ourselves – or each other, have fun with it, it could be a quiz, two fundamental questions: 1) Are you happy with things the way they are? And 2) Do you believe that things could be better?

I know most people want change. I know most people can’t be happy with the current regime. In any electoral process worth having, we might assume that the 3.5 billion people who have as much wealth collectively as the 85 richest people in the world are up for some amendments an’ all. I just used the calculator on my phone to subtract 85 from 3.5 billion and the answer had a letter in it. Even the calculator has gone berserk at this injustice.

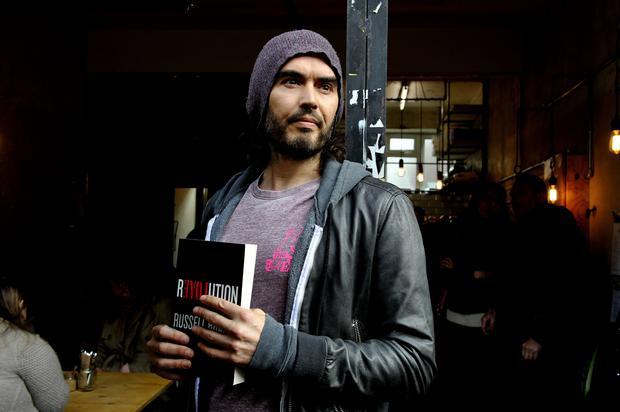

That aside, a significant number of people are not happy with the way things are. I’m not, and I’ve done all right out of this system: I’ve a big house, a nice cat, and when I write books, they’re immediately put on the school curriculum. So this system has not been bad to me. I’ve been given everything I wanted. The problem is, I didn’t really want it. That desire was put there. Who put it there? And why?

And why doesn’t it work? Do you remember when Haiti had that earthquake? You probably don’t, you self-centred swine, and if you do, I bet it’s because of the star-spangled telethon that came in its wake. The telethon is a near-permanent fixture in our culture, and in a way the perfect concoction for a society that wants to release hot little farts of compassion, but without wanting to ever actually follow through. I was invited by George Clooney to participate in this grotesquely beautiful effort to provide aid for the victims of the 2010 disaster, and was instantly told by someone at the agency that attendance was mandatory as it was a good career opportunity. Which I’m sure, as much as the rice and antibiotics, soothed the displaced Haitians. “I’m sorry you lost your house and leg and dog and daughter – here’s some medicine that was purchased in the most glamorous way imaginable, in a format that’s given some Hollywood newcomers a real chance to shine.” (Clooney obviously set up this event with the best of intentions, with incredible effort, using his visibility and luminance to draw attention to the vital need for humanitarian aid. Clearly no one would condemn him for this kindness. It is just unfortunate that when philanthropy meets the machinery of celebrity, it acquires such an unpleasing hue.)

The reason this event was spectacular in the crowded marketplace of televised benefits was because of the sheer density of stars. It was obscene. Like fame porn. As I nervously shuttled through security like a first-day intern into the CBS studios, I was so overwhelmed by the frequency of famous faces in an enclosed space that I almost exploded. What is this tenuous equation between fame and tragedy?

What celestial matchmaker has slung together these mismatched phenomena? Fame to treat famine, fame to treat poverty, fame to take the boredom away. An implausible coupling that advances the benefactor more than the beneficiary. Still, I went anyway; as I say, it was a good opportunity. I’m glad I went, too. It was like Madame Tussauds after a visit from a wizard. It appals me to confess that I don’t recall having any actual connection with the reality of the situation: that a natural disaster had sent a nation spiralling into chaos, disarray and tragedy. In my head, it was kind of like I was a last-minute replacement for the best man at George Clooney’s wedding and had to get to the venue on time at all costs. Which sounds a bit like the plot of a film he’d be in.

I’m not pointing the finger at anyone else, by the way; they may all have been there with the noblest intent. I’m prepared to accept sole responsibility for this hollowness and duplicity; perhaps it was just me who had no visceral, human connection to the suffering. Actually, though, isn’t that was these telethons are for? Not to actualise the disaster, to make it real, feel it, process it and resolve it, but to remove it, package it, give it a framework that is manageable somehow.

Yes, the tectonic plates are colliding and humanity is tumbling into the magma at the Earth’s core, but don’t worry, we’ve got Leonardo DiCaprio on line one. If you’re lucky, you get Leo or De Niro or Pacino or Daniel Day-Lewis or J-Lo or Brangelina. In one little sweep of my eye across a distance of about 12 yards, I was able to assemble the above constellation in some ghoulish, grafted menagerie of fame, the lot of them stacked up in phone banks like really well-groomed battery hens. Like an episode of Celebrity Squares held at Diana’s funeral. Too much. Just too much, and as William Blake has always said, the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. The wisdom reached by excess of this nature is that it’s all fucking bollocks, the celebrity equivalent of making a kid you catch smoking a fag do the whole packet. “So it’s fame you like, is it? Well, how about all the famous people in the world jammed into one, chilled, airless, glass box? Hahahahahahaha!”

Not everyone who called in by phone to pledge their donation was lucky enough to get George or Jack or Al. Some of ’em got me, and after about the third person had indignantly inquired, “Who?” and I had tired of explaining Sarah Marshall and Sachsgate, I just started saying, “Yeah, it’s Spiderman here, how can I help you?” hoping that Tobey Maguire couldn’t hear me.

I know George Clooney is probably a decent geezer an’ all that, and I’m no more condemning him for the vacuity of celebrity-driven humanitarianism than I am David Cameron for capitalism. I’m just saying, how long can you inhabit this sparkling candy palace without wanting to kick down the walls? If you’re not on the inside trying to get out, are you outside trying to get in? Or are you indifferent to the whole charade? Were you never taken in?

Under what circumstances is continuing to live like this the best option? Only if you have no belief that any alternative is possible. Only then. The celebrities feel better for taking part. The callers feel better for donating. The Haitians get a bit of aid they should rightly have been given under the covenant of brotherhood that exists between us all, and we all just smile and pretend there’s no alternative.

There is another way. There is the way. To live in accordance with truth, to accept we are on a planet that has resources and people on it. We have to respect the planet so we can use the resources to nourish the people. Somehow this simple equation has been allowed to become extremely confusing.

If I, so close to the peak, could glean no joy from that rarefied air, the air I was told, as soon as I’d acquired language, would absolve me, if in fact all I gleaned was the view from that peak, the vista true, that the whole climb had been a spellbound clamber up an edifice of foolishness, then what possible salvation can there be for those at the foothills or dying on the slopes or those for whom the climb is not even an option? What is their solution? Well, it’s the same solution that’s available to me, the only solution that will make any of us free. To detach the harness and fall within.

Now that’s what I call an extended metaphor. But none of us wants a boring solution. The Revolution cannot be boring.

There’s more to anarchy than not tidying your bedroom, spitting and having a mohican, David Graeber told me. In fact, it isn’t defiantly disorderly at all; it is society that has no centralised power. David came round my house in east London to talk to me about revolution. I knew immediately that I’d like him – he just had one of those faces.

David is best known for his idea of debt cancellation. Personal debt cancellation used to be a common policy in ancient civilisations; every seven years, all debt was cancelled. The Bible refers to “debt jubilees”, where everyone’s debt would be reset to zero. It’s especially nice that it was called a “jubilee”, creating an even more euphoric sense of carnival. In Islam, too, usury, credit at extortionate rates – like Wonga or whatever offer – is forbidden. So this bizarre-sounding notion has strong historic precedent. It is a mark of how far into materialism we have descended that it seems unfeasible in our world.

David explained that debt repayment has a powerful moral charge in our culture, that people feel ashamed about debt and guilty about non-payment. Seventy-five per cent of Americans are in debt, 40% owing more than $50,000, while an estimated nine million British people are in “serious debt”. What David Graeber, the anarchist, is suggesting is that all personal debt, debt for normal people, is cancelled. Think about it. That means you. All your debt cancelled.

When David said this, I felt excited, like it was naughty, like it shouldn’t be allowed. This is the feeling I still get when I start a car. “I shouldn’t be doing this,” I think, plunging down on the accelerator. The reality is, I shouldn’t be – I’m a terrible driver. My conditioning kicked in when David said that debt cancellation is a contemporary possibility. I nearly told him to shush and looked over my shoulder for a park keeper. Immediately, just by contemplating it, you feel like you’re bunking off school. “We can’t cancel debt – we’ll get the cane.”

I thought about the ramifications. Well, obviously, most people would be thrilled. Tuesday night you go to bed with a credit card bill, mortgage and a bloody headache; Wednesday you wake up with a spring in your step and a pound note in your pocket. What a touch. Obviously this is not such good news for credit card companies and banks; overnight, their entire operation has irrevocably altered. Most of these companies are international, too, so what would the impact be on global finances? I imagine a mainstream economist – and let me tell you off the bat, I’ve no fucking intention of asking one – would say this action would instigate financial meltdown.

What Graeber says in response to this is that $700bn was written off and trillions were lent to banks as the result of the 2008 financial crash. When the reckless and greedy trading, lending and gambling of the financial industry led to an economic breakdown that, if not resolved, would’ve provoked social upheaval, possibly Revolution, the governments of affected nations got together (in a smoky, dim-lit room?) and decided to press reset on the economy. Aside from a few people carrying plants out of their offices in cardboard boxes, I don’t remember there being many consequences at all. Just some people with plants looking confused by a revolving door.

Oh, and 13.1 million American people had their homes foreclosed. Because their debt, it turns out, was real; it was only the debt within the financial sector that was imaginary. It was only the people who generated the crisis who got three magical wishes from an economic genie. There was no abracadabra for ordinary people, they just got abraca-fucked.

So we are not discussing whether or not debt cancellation is a possibility; we know it is, we’ve seen it, they’ve done it. All we are discussing is whom it is possible for. Them or us.

I’ve just typed myself into a revolutionary fervour again. Every so often, the fury at injustice rises up in me and makes me want to smash something or burn something, but nothing in my immediate environment belongs to me, so I have to refrain.